In 1905 Lois Wilson is born into deep poverty in the rural south. Her first paint is the black shoe polish she snitches out of the pantry. Her first paintings are on pieces of scrap tin she picks up from the blacksmith shop of her alcoholic father. Little did she know at the time that she is following in the tradition of Outsider Artists who create art on found objects.

In 1905 Lois Wilson is born into deep poverty in the rural south. Her first paint is the black shoe polish she snitches out of the pantry. Her first paintings are on pieces of scrap tin she picks up from the blacksmith shop of her alcoholic father. Little did she know at the time that she is following in the tradition of Outsider Artists who create art on found objects.

Fayette, with its population of 5,000, is where she spends her childhood. “There was no art, no art interest,” says Wilson. She comes home from grammar school one day to find that her mother has thrown out all her drawings while cleaning the house. Wilson continues, “I can still suffer that moment when I let it come to mind. It acted like a cyclone on my soul.”

Poverty follows her throughout her life. As a child many mornings the only breakfast she has is the watermelon she gets out of the watermelon patch. As a high school student in Fayette, she finds herself in a position of having to earn money. Over the years she does odd jobs to support herself: she works in bookstores and at a factory; she is a draftsman for a landscape architect, a gallery attendant, a salesgirl, and a cat sitter.

Showing early promise, Wilson studies architecture at Auburn University in 1924 on a scholarship. She then studies at an art school in Boston on another scholarship. In 1930 her art education continues in Europe, a gift from a wealthy friend.

In 1935 she settles in New York. Because she served in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II, starting in 1949 for three years she studies at the Art Students League in New York City through her GI Bill of Rights Education benefits.

In 1935 she settles in New York. Because she served in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II, starting in 1949 for three years she studies at the Art Students League in New York City through her GI Bill of Rights Education benefits.

Unable to afford rent in New York City, Wilson moves to Yonkers where they are bulldozing the slums around her. As the city of Yonkers is being torn down and rebuilt, throwing off tons of refuse, every day she goes “junking,” searching for scrap wood, any shape or size, and pieces of furniture that have been crushed by the bulldozer.

Unable to afford rent in New York City, Wilson moves to Yonkers where they are bulldozing the slums around her. As the city of Yonkers is being torn down and rebuilt, throwing off tons of refuse, every day she goes “junking,” searching for scrap wood, any shape or size, and pieces of furniture that have been crushed by the bulldozer.

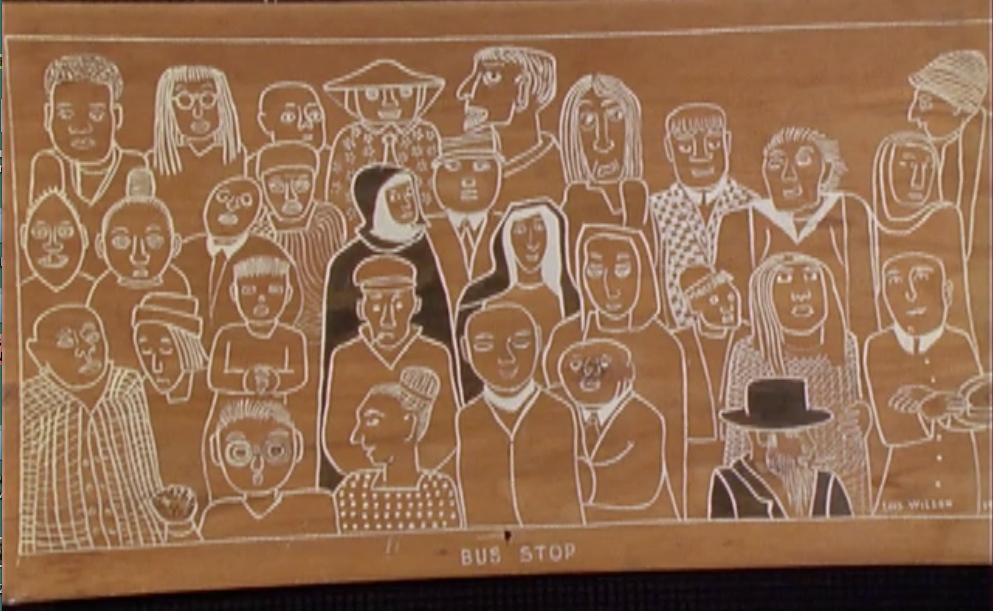

She breaks drawers apart so she will have four flat boards to paint on. “I spend half the night cleaning and sandpapering.” Wilson continues, “I can hardly wait until it is ready to make my drawing on it.”

She paints on sides of drawers, table legs, fan blades, and toilet seats. Many of these works are her white drawings on wood, which she adapted from the Australian aborigines. Many are assemblages such as “The Owl,” made from an old bench support that she found and cut away the rotted part.

Wilson decides to kick out of her head everything she has been taught about art. She says, “I no longer will allow myself to be a ditto artist, copying other artists’ concepts and styles.”

Wilson decides to kick out of her head everything she has been taught about art. She says, “I no longer will allow myself to be a ditto artist, copying other artists’ concepts and styles.”

Like the folk artists she so admires, Wilson spends the rest of her life creating art from found objects.

Living alone with lumber in her bathtub and with junk and art stacked shoulder high, she sees the volume of her own work grow as does the accumulation of art from other artists with whom she barters for their work.

Living alone with lumber in her bathtub and with junk and art stacked shoulder high, she sees the volume of her own work grow as does the accumulation of art from other artists with whom she barters for their work.

With cranes and bulldozers approaching, with her landlord complaining about a fire hazard in her apartment, with bad health and old age upon her, Wilson decides she must get her treasure moved to safety. She turns back to Alabama to find the credibility she did not find in New York.

A correspondence follows with Jack Black, a Fayette newspaperman. Wilson’s passion for art, anti-materialism and the environment impresses Black. He responds to her hope that her art collection might become a legacy and an inspiration to young people.

Wilson writes Black that she wants her hometown to have the collection if he will keep it intact and provide permanent space for its showing in Fayette. He gives his word to her that he will somehow set up a permanent exhibition.

In 1969 the Wilson Collection finally arrives in Fayette. Opening crate by crate, Black becomes more and more dazzled by the quality and diversity of the treasure she has handed off to him. Wilson ultimately gives to Fayette 2,600 pieces of her own and of other artists’ work.

Black spends the next 35 years of his life shepherding the Fayette Art Museum from its fragile birth to its solid presence as an icon of Southern pride in its arts. He dies in 2004 after having completed his most cherished accomplishment.

The Fayette Art Museum, which began with the Wilson Collection in 1969, has since become a magnet for working artists. It holds an annual August Arts Festival featuring 125 well-known artists from around the Southeastern U.S. and more than 7,000 patrons. Its collection includes works of widely regarded local artists such as Jimmy Lee Sudduth who is featured in the film.

Sudduth, the black artist-musician who produced a wealth of true American folk art, worked with mud for paint. He was revered by Wilson, interviewed on the national morning show NBC Today, honored at the White House and represented in the Smithsonian and other leading museums.

Sudduth, the black artist-musician who produced a wealth of true American folk art, worked with mud for paint. He was revered by Wilson, interviewed on the national morning show NBC Today, honored at the White House and represented in the Smithsonian and other leading museums.

The Fayette Art Museum has also put Fayette on the tourist map ever since National Geographic flagged the museum as a regional attraction.

Lois Wilson died poor and obscure in Yonkers, New York, in 1980 at the age of seventy-five. The beauty of her art and the vision of the woman live on.